Mental Health

Services and

Schools Link Pilots:

Evaluation report

Final report

February 2017

Contents

List of figures 5

List of tables 6

Acknowledgements 7

Glossary 8

A note on report terminology 9

Executive summary 11

Overview of the pilots 11

Key findings 11

Aims and scope of the pilot programme 12 Design and set-up of the pilot programme 13 Lessons learned from implementation 13

Joint planning workshops 13

Single point of contact arrangements 14

Sustainability 15

Conclusions and recommendations 15

Methodology 17

1.0 Introduction 18

Background to the pilot programme 18 Aims and objectives of the pilots 20

Overview of the evaluation 23

Methodology 23

Structure of the report 27

2.0 Design and set-up of the pilot programme 28 Local context prior to the pilot programme 29 Challenges and barriers to accessing specialist support 31

Pilot set-up arrangements 37

Identifying and engaging schools 39

Early pilot development 40

3.0 Lessons learned from implementation 43

Learning points and areas for development 49 Staffing and governance arrangements 51 Defining the ‘single-point-of-contact’ role 52 NHS CYPMHS – pilot staffing arrangements 53 Schools – pilot staffing arrangements 54 Roles and responsibilities in practice 55 Testing and implementing the single-point-of-contact role 59

Delivery of training in schools 61

Examples of joint working between schools and NHS CYPMHS 62 Communication and reporting arrangements 64 Barriers and enablers to effective delivery 66

4.0 Impacts and outcomes 70

Professional knowledge, awareness and understanding 73 Joint professional working and communication 77 Referrals for specialist support – pilot schools 80

Service and systems outcomes 85

Area-level capacity-building 85

School-level capacity-building 87

NHS CYPMHS capacity-building 91

5.0 Sustainability of the pilot models 92 Demand for sustaining NHS CYPMHS and school links 93 Scaling up the models – challenges and potential solutions 95 Successful examples of early mainstreaming 99 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 103

Overall achievements 103

Effectiveness of programme implementation 103

Impacts and outcomes 104

Key messages for policy and practice 106

Critical success factors 106

Appendix 2: CASCADE framework for collaborative working between schools and mental

List of figures

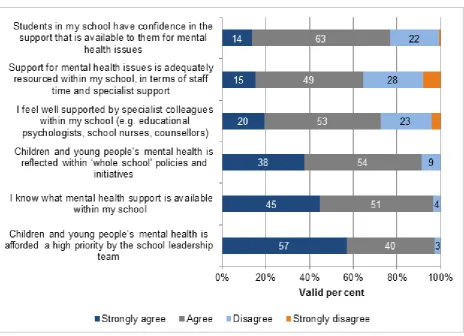

Figure 1 To what extent do you agree with the following statements about mental health support within your school? (school lead contacts) 33

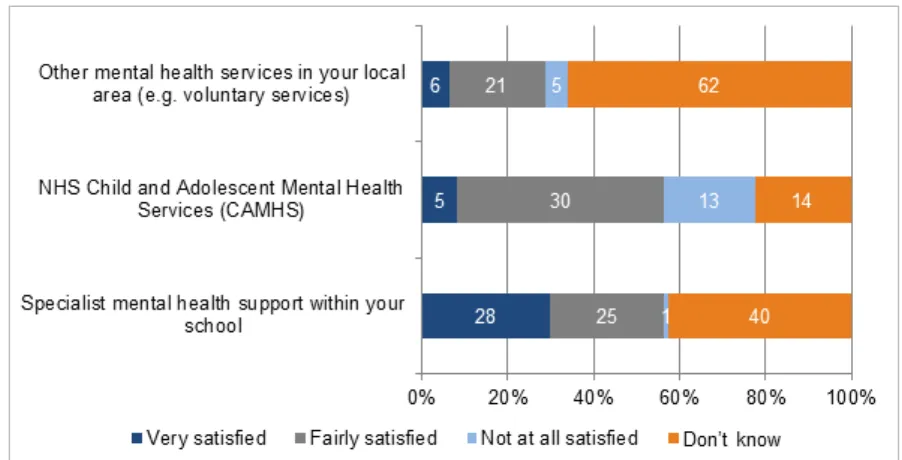

Figure 2 Overall, how satisfied are you with the way that referrals were handled during the past school year? (school lead contacts) 34

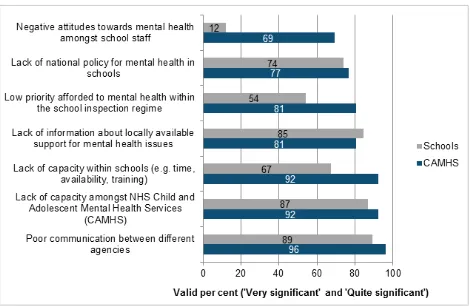

Figure 3 Significance of potential barriers to providing effective mental health support (combined – school and NHS CAMHS/CYPMHS lead contacts) 35

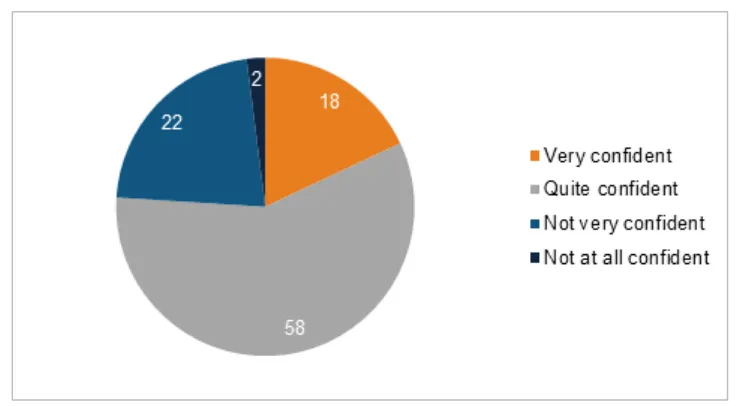

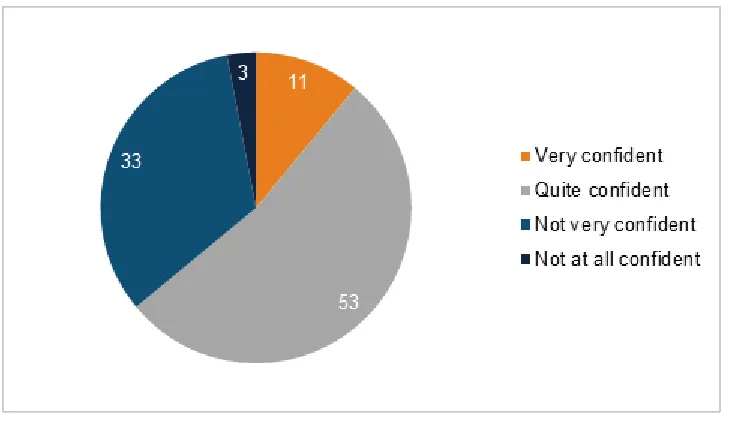

Figure 4 How confident do you feel about talking to students about their mental health and well-being? (whole school survey) 36

Figure 5 How confident do you feel about talking to parents and carers about the mental health and well-being of students in your school? (whole school survey) 37

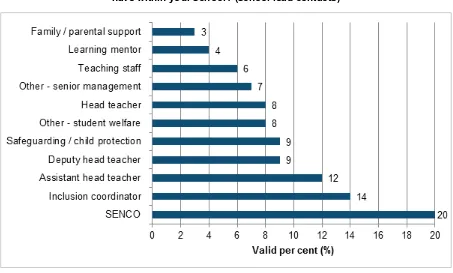

Figure 6 In addition to being a lead contact for the mental health pilot, what other role(s) do you have within your school? (school lead contacts) 54

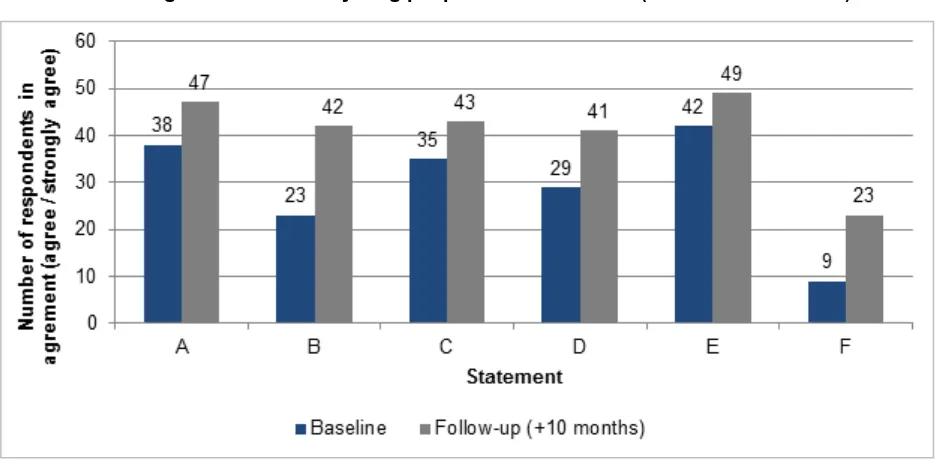

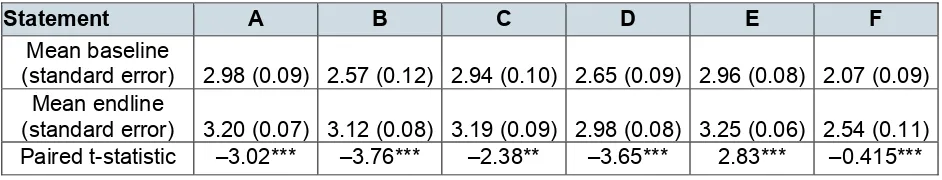

Figure 7 To what extent would you agree/disagree with the following statements about your knowledge of children and young people’s mental health? 73

Figure 8 Approximately how often did you have contact with the following mental health professionals – NHS CYPMHS (school lead contacts) 77

Figure 9 Approximately how often did you have contact with the following mental health professionals? (school lead contacts) 78

Figure 10 Which of the following types of contact did you have with these mental health professionals – NHS CAMHS? (school lead contacts) 79

Figure 11 Overall, how satisfied are you with the way that referrals to NHS CAMHS were handled, during the past school year? (school lead contacts) 81

List of tables

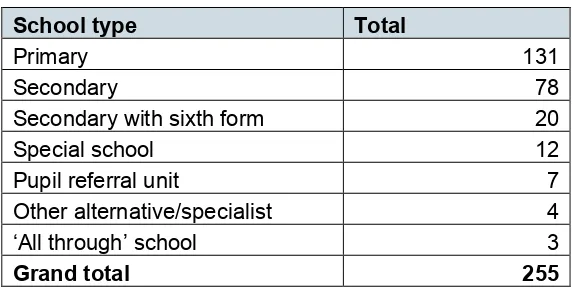

Table 1 Pilot schools according to type of school 40

Table 2 Pilot implementation – 3 different types of delivery model 57

Table 3 Average rating of knowledge and confidence: baseline and +10 (school lead

contacts) 74

Table 4 Satisfaction with referral handling (school lead contacts) 80

Table 5 Case study: 'before and after' – 2 referrals by the same school 84

Table 6 CASCADE data – scoring by indicator (phases 1, 2 and change) 87

Table 7 Average rating of mental health support in the pilot schools (school lead

contacts) 88

Table 8 Types of mental health support offered within pilot schools (school lead contacts) 89

Table 9 Profile of pilot areas featured within the evaluation report 110

Table 10 Achieved sample for qualitative fieldwork 111

Table 11 Comparison of baseline and follow-up survey schools – by pilot area 112

Table 12 Comparison of baseline and follow-up survey schools – by school type 113

Acknowledgements

The Research Team at Ecorys would like to thank Catherine Newsome, Viv McCotter, Alison Venner-Jones at the Department for Education, Michelle Place and Steve Jones at NHS England, for their support throughout the evaluation. Further thanks go to Dr

Miranda Wolpert, Dr Melissa Cortina, Jaime Smith and colleagues at the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families (AFNCCF) for ongoing support during the implementation of the pilots and for contributions to the Evaluation Steering Group.

We would also like to thank all of the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), NHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (CYPMHS), schools and partner organisations who elected to participate in the evaluation and who contributed their views and experiences. Without them, this report would not have been possible.

The Ecorys researchers undertaking the case-study fieldwork included Rachel Blades, Laurie Day, Jenny Williams, Catie Erskine, James Ronicle and Kate Merriam. The

Glossary

Abbreviation Definition

ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

AFNCCF Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families ASD autistic spectrum disorder

CAMHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services CAPA Choice and Partnership Approach

CBT cognitive behavioural therapy CCG Clinical Commissioning Group CYP children and young people’s

CYPMH Children and Young People’s Mental Health

CYPMHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services DBT dialectical behaviour therapy

DfE Department for Education

EBD emotional and behavioural difficulties FE further education

FSW family support worker FTE full-time equivalent GP general practitioner

IAPT Improving Access to Psychological Therapies MARAC Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference MHSDS Mental Health Services Data Set

NHS National Health Service

PEVP permanently excluded and vulnerable pupils PMHW primary mental health worker

SEN special educational needs

SENCO special educational needs co-ordinator SFT solutions-focused therapy

SLT senior leadership team SPOC single points of contact

TaMHS Targeted Mental Health in Schools VCS voluntary and community sector

A note on report terminology

Mental health provision for children and young people in England is provided under the umbrella of Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (CYPMHS). The CYPMHS framework incorporates all professionals working with children and young people, from universal provision through to specialist inpatient and outpatient services.

CYPMHS in England have historically been planned and funded under the banner of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and organised around four ‘tiers’, corresponding with different levels of need or complexity1. These arrangements are

acknowledged to be complex, and the 2015 report from the Government’s Children and Young People’s Mental Health Taskforce, Future in Mind, identified a priority to urgently review the existing framework, aspiring towards a “system without tiers2”. Many areas are

now moving away from this method of organising services, developing models such as 0–25 integrated pathways or adopting the THRIVE service framework3.

The pilot programme was funded to strengthen joint working arrangements between schools and specialist CYPMHS. For the purpose of consistency in the report, we have made a distinction between the following:

• NHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (NHS CYPMHS – statutory children and young people’s specialist mental health services funded by the NHS and commissioned locally via Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), who were the recipients of the pilot funding from NHS England and who provided the primary mental health workers to link with pilot schools

• Other Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (Other CYPMHS – all other professionals within the wider network of organisations working with children and young people at different levels of need, including but not restricted to: school nurses, educational psychologists, counsellors and provision funded and provided via the voluntary and community sector (VCS)

The decision to replace the term CAMHS with CYPMHS throughout the report was taken by the Evaluation Steering Group in January 2017, to better reflect the feedback from children and young people that was incorporated in the Future in Mind priorities, and to avoid the risk of misunderstanding surrounding the CAMHS Tiers. As the term ‘NHS

1 The four tiers include: Tier 1: universal services, Tier 2: targeted services, Tier 3: specialist services and

Tier 4: specialised CAMHS. Further explanation of the framework can be found in the following report: CAMHS Tier 4 Report Steering Group. CAMHS Tier 4 Report. 2014. London: NHS England (p. 11). (Accessed 3 January 2017)

2 Department of Health. Future in mind: Promoting, protecting and improving our children and young

people’s mental health and wellbeing. 2015. London: NHS England (p. 41). (Accessed 3 January 2017)

3 The THRIVE Framework is a conceptual model for ensuring needs-led service planning and review for

children and young people’s mental health services. It is supported by training, resources and a community of practice. (Accessed 24 January 2017)

CAMHS’ is still in widespread use, and was included within the original primary research tools for the evaluation, this terminology has been retained where the authors are

reporting upon verbatim quotes or survey questions within the report.

Executive summary

In summer 2015, NHS England and the Department for Education (DfE) jointly launched the Mental Health Services and Schools Link Pilots. The pilot programme was

developed in response to the 2015 report of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Taskforce, Future in Mind, which outlined a number of recommendations to improve access to mental health support for children and young people.

Overview of the pilots

A total of 22 areas, incorporating 27 CCGs and 255 schools, were funded to establish named lead contacts within NHS CYPMHS and schools. They also participated in 2 joint planning workshops, involving other professionals from their local CYPMHS network. These included, but were not restricted to, school nurses, educational psychologists, counsellors and voluntary and community sector organisations (VCSOs). The local pilots were led by CCGs, often with active involvement from local authorities.

The joint planning workshops were facilitated by a consortium led by the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families (AFNCCF), using a framework developed specifically for the pilot programme (CASCADE) and involving a combination of reflection, action planning and review to benchmark local collaborative working.

In September 2015, Ecorys (UK) was commissioned by the DfE to undertake an

independent evaluation of the pilot programme. A mixed methods design was deployed, incorporating survey research, research observations and qualitative case studies in a sample of 10 areas. The data collection took place between September 2015 and 2016.

Key findings

Overall, the evaluation found that the pilots had considerable success in strengthening communication and joint working arrangements between schools and NHS CYPMHS. This was often the case even where relationships were said to have been weak at the start of the pilot programme, although the extent of change varied between pilot areas.

At a programme level, the evaluation found quantifiable improvements to the following self-reported outcome measures, between a baseline and follow-up at +10 months:

• frequency of contact between pilot schools and NHS CYPMHS

• satisfaction with communication and working relationships between pilot schools and NHS CYPMHS

• understanding of the referral routes to specialist mental health support for children and young people in their local area among school lead contacts

There was a smaller increase in the frequency of contact between school lead contacts for the pilots and other school-based mental health professionals. These varied between schools but included educational psychologists, counsellors and school nurses.

While harder to quantify, the interviews strongly suggest that the programme contributed towards improvements in the timeliness of referrals and helped to prevent inappropriate referrals within many areas. This was enabled by schools’ improved understanding of pathways and ongoing contact with NHS CYPMHS. The qualitative interviews show that many of the pilots facilitated direct referrals to the NHS service and discouraged

unnecessary indirect referrals via GPs, where this local flexibility was available. They sometimes helped to improve the flow of information beyond the initial referral. In this context of improved capability in schools, closer joint working and more timely direct referrals, it was noteworthy that, at programme level, there was not an overall increase in the level of referrals, although unmet need was identified within some pilot schools.

There was also quantifiable evidence of improvements for all knowledge and awareness-related measures among other school staff. There was a strong indication that many schools had cascaded the benefits of the programme beyond the lead contact and used their pilot to complement existing funding and support for mental health and well-being.

Aims and scope of the pilot programme

The overall aim was to test the extent to which joint professional working between schools and NHS CYPMHS can improve local knowledge and identification of mental health issues and improve the quality and timeliness referrals to specialist services.

The pilot programme centred on 2 joint planning workshops for local stakeholders from CYPMHS in each of the 22 areas. The workshops were designed and facilitated by a consortium led by the AFNCCF, using a bespoke framework (CASCADE).

The pilot programme was implemented in 3 phases:

• phase 1: forming partnerships – workshop 1 (September to December 2015)

• phase 2: embedding and building sustainability – workshop 2 (January to March 2016)

• phase 3: supporting ongoing learning through 2 national events (May 2016).

Design and set-up of the pilot programme

Strong CCG strategic leadership was a key factor in ensuring strategic buy-in across local CYPMHS, and schools and colleges, within challenging timescales. Pilot sites where CCGs had already developed this leadership role, often in close partnership with local authorities, were better placed to progress the pilot and to broker the sometimes-difficult initial conversations between schools and NHS CYPMHS at the start of the programme.

Most areas approached the pilot with a view to complementing activities identified in Children and Young People’s Mental Health (CYPMH) and well-being local

transformation plans. Strong synergies were also identified with emotional well-being and resilience work in schools. The opportunity was welcomed to add a stronger ‘clinical’ mental health dimension to this existing offer.

There is some evidence that the bidding timescales favoured schools that were already engaged with NHS CYPMHS to some extent and that the pilot schools were not

necessarily representative of the wider population. Even so, here was a good mix of school types across the pilot programme. While further education (FE) colleges were not excluded from taking part in the pilot, they were not represented in this phase of piloting.

Lessons learned from implementation

Joint planning workshops

The majority of interviewees reported that the joint planning workshops met their expectations. Participants generally welcomed the combination of factual information, benchmarking and action planning using CASCADE. A few areas commissioned further workshops from the consortium led by the AFNCCF, to extend the opportunity to

additional schools.

Single point of contact arrangements

Local NHS CYPMHS recruited or seconded one or more primary mental health workers to perform the lead contact role. The approach was typically guided by decisions about the feasible offer of time per school. Most schools identified an operational lead contact with student welfare responsibilities, such as a SENCO or inclusion co-ordinator,

reporting to the senior management team, although these roles were occasionally combined.

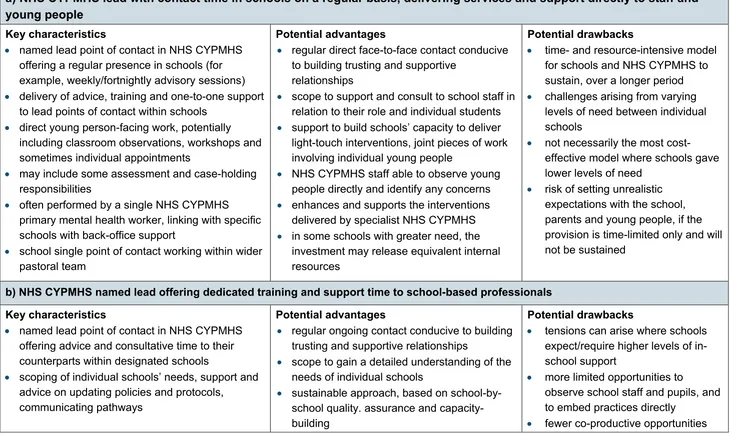

The specific responsibilities of the NHS CYPMHS lead point of contact varied between the pilots, but it was possible to group them according to 3 main types:

• NHS CYPMHS named lead with contact time in schools on a regular basis, delivering services and support directly to staff and young people

• NHS CYPMHS named lead offering dedicated training and support time to school-based professionals

• NHS CYPMHS named lead or duty team with designated responsibilities for the pilot, offering a single point of access

No single model emerged as being the most effective, as pilots developed their approach to suit local circumstances, priorities and aims. However, a shared commitment from schools and NHS CYPMHS was essential for embedding the joint working arrangements, alongside backing from senior management teams across both sets of agencies to also ensure that staff had sufficient time to participate.

A regular presence from NHS CYPMHS in schools enabled workers to support and consult to school staff, and to work with pupils directly. High levels of school-based support were costly, however, and some areas raised concerns about the sustainability of the external support, reflecting the need for a strategic, system-wide approach. The evaluation highlighted the potential value of potentially undertaking further work to model the return on investment and potential educational gains that schools and colleges might see in the event of establishing successful models of joint working.

Sustainability

NHS CCG commissioners, NHS CYPMHS and schools were strongly supportive of sustaining effective channels of communication, but there were mixed views on how single points of contact (SPOC) might be funded beyond the programme. Many of the pilot areas were exploring options for working at scale, without diluting contact time with schools. This generally included a combination of the following:

• a traded offer, whereby a proportion of the costs were passed on to schools; this was sometimes based on a tariff system or menu of options

• cluster or locality-based support, whereby NHS CYPMHS lead contacts linked with a number of schools via established local multi-agency teams

• a single point of access for schools, generally based around a triage and duty system, with NHS CYPMHS workers responding on a rota basis; some areas had combined this with a telephone helpline and email address for professionals

• making full use of the wider network of NHS CYPMHS – rather than focusing on solely on specialist NHS CYPMHS and schools; some areas were reviewing the potential for educational psychologists, school nurses and VCSOs to an active contribution towards widening access to mental health support within schools

• training and capacity-building, often based around a foundation tier of training for potentially large numbers of schools, with the option of higher-level training

A smaller number of areas had already secured the funding and political commitment from the school community and NHS CCG with local authority support to scale up joint working when the evaluation fieldwork took place.

Conclusions and recommendations

At a national level, the pilot programme very much demonstrates the potential added value of providing schools and NHS CAMHS with opportunities to engage in joint planning and training activities, improving the clarity of local pathways to specialist mental health support, and establishing named points of contact in schools and NHS CAMHS. At the same time, the evaluation has underlined the lack of available resources to deliver this offer universally across all schools at this stage within many areas.

On this basis, the evaluators conclude that there is a good foundation for the Department of Health, NHS England and the DfE to consider how the learning from the pilot

programme might be shared, disseminated and scaled up, beyond the 22 areas that participated in the pilot programme. This might include the potential collation and

Critical success factors for establishing effective joint working

arrangements between schools and NHS CYPMHS

a. a strategic role for the CCGs and LAs in providing leadership and mobilising different partners from across the local network of CYPMH services

b. a forum for collective planning and needs analysis at a local area level, linking into wider strategic commissioning processes and to the CYPMH and Wellbeing Local Transformation Plan

c. mapping of interventions and professional expertise, to ensure the best use of available resources within the local CYPMH network

d. clarity and common understanding of pathways and criteria for specialist support and accompanying tools and guidance to make this process as easy as possible; this includes agreement on common terminology and outcome measures

e. a single point of access in NHS CYPMHS for information and advice about mental health issues, supported by central telephone and email contact points

f. a thorough initial scoping review to determine schools’ needs – including their relative needs – for specialist support, prior to determining the necessary staffing commitment by NHS CYPMHS

g. a minimum commitment from schools to identify a suitable lead point of contact, with support from the Senior Management Team to ensure that they have sufficient time to attend joint planning and training activities with NHS CYPMHS h. a review within CYPMH Local Transformation Plans – including at least the CCG,

schools and NHS CYPMHS; to determine and commission the appropriate CYPMHS support offer and how this is apportioned between schools

i. a commitment in the school development plan to sustain the SPOC arrangements and to develop a mental health and well-being policy

j. monitoring and self-evaluation of joint working arrangements, to review what works well/less well; to appraise the quality and appropriateness of referrals under the new working arrangements and to make adjustments as necessary k. access to further training and bespoke guidance or support for schools, as

identified through self-evaluation, via a menu of support from CYPMHS

l. quarterly or biannual mental health forums or network meetings, to ensure that all schools and other CYPMHS providers, including NHS CYPMHS, educational psychologists, school nurses, counselling services and VCSOs, have an

Methodology

The evaluation was funded between September 2015 and December 2016 to provide an assessment of the effectiveness of the design and implementation of the pilot programme and the outcomes achieved within the first 12 months for data collection.

A mixed methods approach was used, comprising pre/post online surveys with SPOC in schools4, other school staff5 and NHS CYPMHS6 (baseline prior to the initial workshops

and follow-up at +10 months); a snapshot ‘exit’ survey of other local key stakeholders7;

in-depth qualitative telephone interviews with NHS CYPMHS lead contacts; workshop observations; and 10 local area case studies8. Further details on sampling, data

collection, analysis and reporting are provided within the main report.

The evaluation design and achieved sample sizes were sufficiently robust to allow for a good level of confidence in the results. The comparison of survey outcomes relates to the cohort of schools participating in the pilot programme. Limitations to the comparability and availability of administrative data held on statutory NHS CYPMHS entailed that it was not possible to undertake a quasi-experimental impact evaluation as part of the study.

4 School lead contact survey, baseline n = 166 schools, follow-up n = 49 schools.

5 Administered within a sub-set of 48 pilot schools, baseline n = 552 individuals, follow-up n = 95

individuals.

6 NHS CYPMHS lead contact survey, baseline n = 18 respondents, follow-up n = 2 respondents. 7 Administered at a single point in autumn 2016, achieved sample = 68 respondents.

8 The qualitative research covered 15 of the 22 pilot areas, with a total of n = 124 respondents through the

combined telephone interviews and case-study interviews. The 10 case studies were sampled purposively on the basis of socio-demographic characteristics, types of schools, baseline position for joint professional working (high/mixed/low) and areas of potential good practice. Each case study comprised interviews with the CCG strategic lead, NHS CYPMHS strategic and operational staff, school lead contacts and teaching staff, and partner organisations from CYPMHS.

1.0 Introduction

In September 2015, Ecorys (UK) was commissioned by the Department for Education (DfE) to undertake an independent evaluation of the Mental Health Services and Schools Link Pilots. This final report presents the summative findings from the evaluation, which was carried out between September 2015 and November 2016, covering all 22 pilot areas. A mixed methods approach was deployed, using a

combination of desk research, surveys of representatives from schools, NHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (CYPMHS9 and other local stakeholders and

qualitative case-study research.

In this introductory chapter, we give an overview of the background to the pilot

programme, its aims and objectives, and how it was structured. We then go on to explain the aims and research methods that were deployed for the evaluation, and we outline the data caveats and limitations framing the analysis within the report.

Background to the pilot programme

In September 2014, the Government established the Children and Young People’s

Mental Health Taskforce10, bringing together experts on children and young people’s

mental health including children and young people, with leaders from key national and local organisations across health, social care, youth justice and education sectors. The remit of the Taskforce was to identify what needs to be done to improve children’s and young people’s mental health and well-being, with a particular focus on making it easier to access help and support, and to improve how CYPMHS are organised, commissioned and provided.

Published in March 2015, the Taskforce report, Future in Mind11 outlined a number of

recommendations to help improve access to effective support for children and young people. The recommendations included the establishment of a named point of contact within specialist NHS CYPMHS and a named lead within each school. The named lead in schools would be responsible for mental health, developing closer relationships with NHS CYPMHS in support of timely and appropriate referrals to specialist services. The report also recommended the development of a joint training programme for named school leads and NHS CYPMHS. The original proposal is outlined in the box below.

9 Refer to the ‘Note on Terminology’ at the start of this report for a full explanation of terms in use.

10Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Taskforce: Terms of Reference. (Accessed 3

January 2017)

11 Department of Health. Future in mind: Promoting, protecting and improving our children and young

people’s mental health and wellbeing. 2015. London: NHS England. (Accessed 3 January 2017)

In early summer 2015, NHS England and DfE asked for expressions of interest from CCGs to join with local specialist NHS CYPMHS and schools to pilot the named lead approach and a joint training programme. Over 80 expressions of interest were received. A total of 22 areas (27 CCGs) and 255 schools were selected.

The Taskforce report builds on a longstanding recognition of the challenges faced by CYPMHS in England. An independent review of CYPMHS commissioned by NHS England12 and evidence presented at the 2014 House of Commons Health Committee’s

inquiry13 each indicated an urgent need for improvements to the timeliness, quality and

accessibility of specialist support for mental health issues and a whole-system response, including a more active role for schools and other CYPMHS. These findings are

supported by previous research into school-based interventions, which identified a need

12 CAMHS Tier 4 Report Steering Group. CAMHS Tier 4 Report. 2014. London: NHS England. (Accessed 3

January 2017)

13 House of Commons Health Committee. Children's and adolescents' mental health and CAMHS:

Government Response to the Committee's Third Report of Session 2014–15. 2015. (Accessed 3 January 2017)

Taskforce proposals for the single points of contact (SPOC)

We propose the following to improve communication and access:

i. Create an expectation that there is a dedicated named contact point in targeted or specialist mental health services for every school and primary care provider, including GP practices … Their role would be to discuss and provide timely advice on the management and/or referral of cases, including consultation, co-working or liaison. This may include targeted or specialist mental health staff who work directly in schools/GP practices/voluntary sector providers with children, young people and families/carers.

ii. Create an expectation that there should be a specific individual responsible for mental health in schools, to provide a link to expertise and support to discuss concerns about individual children and young people, identify issues and make effective referrals … This individual would make an important contribution to leading and developing whole school approaches.

iii. Develop a joint training programme for named individuals in schools and mental health services to ensure shared understanding and support effective

communications and referrals.

Source: Department of Health (ibid., 2015, p. 42)

“… to prioritise improved relationships and referral routes between schools and specialist CAMHS” (p. 3).14

Aims and objectives of the pilots

The overall aim of the pilot programme was to test how or whether training and

subsequent joint professional working between schools and NHS CYPMHS can improve local knowledge and identification of mental health issues, and improve the quality and appropriateness of referrals to specialist services. Specifically, the programme aimed to:

• improve joint working between school settings and specialist NHS CYPMHS

• develop and maintain effective local referral routes

• test the concept of a lead contact in schools and specialist NHS CYPMHS

The pilot programme centred on 2 joint professional planning and development

workshops for local stakeholders from CYPMHS in each of the 22 participating areas, including CCGs, local authorities, NHS CYPMHS, pilot schools and other key partner organisations such as Educational Psychology, School Nursing Services and VCSOs.

The workshops aimed to contribute towards the following outcomes:

• develop a shared view of the strengths and limitations and capabilities and capacities of education and mental health professionals

• develop knowledge of resources to support the mental health of children and young people

• make more effective use of existing resources

• improve joint working between education and mental health professionals

The workshops were facilitated by a consortium led by the AFNCCF, using a framework developed specifically for the pilot programme (CASCADE) and involving a combination of reflection, action planning and review to benchmark local collaborative working using a number of key criteria. A summary of the CASCADE framework can be found at Annex 2.

The pilot programme was implemented in 3 phases, as follows:

• Phase 1: forming schools and children and young people’s mental health partnerships – workshop 1 (September to December 2015)

• Phase 2: embedding partnerships and building sustainability – workshop 2 (January to March 2016)

14 Wolpert M and others. Me and My School: Briefing Note from the National Evaluation of Targeted Mental

Health in Schools. 2011. London: Department for Education. (Accessed 3 January 2017)

• Phase 3: supporting ongoing learning and the development of best practice and ensuring ongoing sustainability through 2 national events (May 2016)

NHS England made funding of £50,000 available per CCG, to cover NHS CYPMHS capacity. CCGs were expected to match-fund this amount. Funding of £3,500 was made available per school to backfill staff time.

Roles and responsibilities

Roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders for the pilots

CCGs

CCGs were responsible for identifying an overall lead; typically the CCG

commissioning lead for CYPMHS, to co-ordinate and act as the overall point of contact for the pilot. Specifically, their role was to:

• commission NHS CYPMHS to participate in the pilot and link with schools

• organise and attend both workshop days, ensuring that representatives from the CYPMHS network were invited, and building in local elements to help support relationships and reflect local circumstances

• develop and deliver a presentation at the first workshop that outlines how services are currently working together in their area, what their transformation plans

involve and what their vision is for the pilot, and developing joint working practices.

• report pilot progress – at the midpoint and at the end of pilot

NHS specialist CYPMHS

NHS CYPMHS were tasked with identifying a named lead(s) to work with each school and oversee operational and organisational issues. Specifically, their role was to:

• participate in the pre and post requirements for the workshops and attend the national events in phase 3 of the pilots to share learning

• work with schools and health colleagues to develop closer links and protocols

• participate in the process and impact evaluations of the pilot, for example by completing baseline and follow-up surveys, interviews and providing other data including after the end of the pilot. Schools and CCGs may be asked to take part in follow-up surveys and questionnaires up to 1 year after the pilots are completed

Schools

Each school was required to nominate a lead person with an overview of mental health issues within their school, to fully participate in the training and the development of the joint working models. This could be a member of the leadership team or someone who has a mental health or well-being role, special educational needs co-ordinators

(SENCOs), education welfare officers, staff with a pastoral lead or educational psychologist where they are employed by the school. Specifically, their role was to:

• attend both workshop sessions, bringing a member of the senior leadership team

• commit to working with NHS CYPMHS professionals to agree joint working and develop shared protocols

• participate in the pre and post requirements for the workshops and attend the national events in phase 3 of the pilots to share learning

Overview of the evaluation

The evaluation aimed to provide an independent assessment of the following:

• The effectiveness of the design and implementation of the Mental Health Services and Schools Links pilot programme, and of the 22 individual local pilots, including:

o challenges and lessons learned from setting up the pilots

o success factors for engaging schools and other key stakeholders

o staffing models developed by schools and NHS CYPMHS and their effectiveness

o lessons learned from planning and implementing the workshops

o sustainability and potential for wider roll-out

• The outcomes achieved within the 12-month time frame for data collection, including the extent to which the pilots resulted in improvements, were as follows:

o knowledge and awareness of mental health issues

o changes to joint working between schools and NHS CYPMHS

o timeliness and appropriateness of referrals from schools to NHS CYPMHS

o wider changes to the culture around mental health in schools

o service and systems improvements in NHS CYPMHS and specialist services

The evaluation covered the SPOC in schools and NHS CYPMHS, and the joint workshops (phases 1 to 3). It also aimed to assess the extent to which the pilots facilitated joint professional working across all CYPMHS within the participating areas, including non-NHS funded services.

Methodology

A mixed methods approach was used for the evaluation, including quantitative and

qualitative data collection and analysis within a framework mapped to the evaluation aims and objectives, and a final synthesis of the evidence. The main elements included:

• Quantitative survey research – four sets of online surveys were designed, piloted and implemented within the 22 pilot areas:

o Pre and post surveys of the SPOC in schools and NHS CYPMHS for the pilot programme, to measure changes over time in levels of knowledge and awareness and joint professional working, using Likert-scale classifications and data on numbers of consultations and referrals. The baseline survey took place in autumn 2015 (n = 166 schools, and n = 18 NHS CYPMHS), with follow-up at +10 months (n = 49 schools, and n = 2 NHS CYPMHS).

senior managers, to teachers and support staff. The baseline survey was

conducted within 1 month of the first workshop (n = 552 individuals, from n = 48 schools), with follow-up at +10 months (n = 95 individuals, from n = 8 schools).

o Snapshot survey of other local stakeholders within the pilot sites, to test levels of awareness of the pilot programme, levels and scope of involvement, and views on the effectiveness and outcomes from the local pilots. The survey took place in autumn 2016 (n = 68) alongside the follow-up surveys with schools and NHS CYPMHS lead contacts. The sample was sourced from updated contact details provided to NHS England by CCGs in May 2016.

• Qualitative telephone interviews with NHS CYPMHS lead contacts – in-depth interviews were conducted with NHS CYPMHS lead contacts (n = 15) in autumn 2015, exploring early lessons learned from setting up the pilot; historical

arrangements for working with schools and other organisations within local

CYPMHS networks, and expectations for the pilot. The interviews were also used to scope the availability of relevant administrative data held on consultations, referrals and other key metrics.

• Structured research observations – a sample of (n = 8) workshops were observed in autumn 2015 and spring 2016 to gain a deeper understanding of the context for joint professional working in those areas and to explore the challenges and successes from planning and delivering the workshops. The AFNCCF also provided data from assessments made using the CASCADE framework for all 22 pilot areas.

• Case-study visits to 10 x pilot sites – conducted in summer and autumn 2016, to explore lessons learned from implementation, successes, challenges and how these were overcome, and plans for wider roll-out. Each case-study visit comprised qualitative interviews and focus groups with key strategic and operational

Analysis of evaluation data

The quantitative survey data was extracted and cleaned before matching the baseline and follow-up responses to measure change across different outcome measures. The results were then compared by respondent type and area. Paired t-tests15 were used to

test for statistical significance and to establish the confidence levels in the results.

The evaluation included a feasibility study for undertaking a comparison of outcomes16

between pilot schools and a matched comparison group of non-pilot schools, using a quasi-experimental design. The feasibility study concluded that this strand was not feasible, owing to the fact that referral data cannot be disaggregated by individual school within most local NHS CYPMHS. The new national Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS17) was considered but was found to be at an early stage of implementation.

The notes from the qualitative interviews were entered into a structured grid, based on the agreed topic framework, and supplemented with verbatim quotes and examples from the transcribed interviews. A thematic analysis was undertaken, to manually compare and contrast the views of the different respondents under common topic headings from the qualitative interviews. Attention was given to key similarities and differences in perspectives, according to pilot area, stakeholder type and professional roles. The findings from the interviews and case-study research were then triangulated with the survey data, to establish the degree to which the different data sources support or refute each other. Emerging themes were discussed with the steering group at the interim reporting stage, with feedback and adjustment prior to final reporting.

Further details on the qualitative sample can be found in Annex 1 (A1.2).

Interpreting the results

The qualitative strand of the research was based on interviews with NHS CYPMHS representatives from 15 of the 22 pilot areas in autumn 2015 who opted to take part, and with a wider range of key stakeholders within the 10 case-study pilot areas in autumn 2016, including representatives from CCGs, pilot schools and partner organisations such as educational psychologists, school nurses and VCSO mental health specialists (n = 124 individual respondents). The ability to sample the case-study areas and schools using the surveys and workshop data allows for a good level of confidence in the results. As with all case-study research, the findings do not claim to be exhaustive, and the case studies do not fully document more recent developments in the remaining pilot areas.

15 T-tests were used to compare the quantitative variables in the data, thereby enabling us to go beyond

comparison of sample means to make inferences generalisable to the populations of interest

16 The outcome measures of interest included referral rates, acceptance rates and conversion rates (from

schools to specialist NHS CAMHS).

17Available online (Accessed 5th January 2017)

The quantitative baseline survey of school lead contacts was completed by almost two-thirds of all pilot schools (65%, or 166 out of 255 pilot schools), thereby giving a good level of statistical confidence in the results. The response was lower at follow-up stage (49 respondents) but nonetheless proved sufficient to measure statistically significant changes for a wide range of outcome variables. A comparison of the school sample at baseline and follow-up stage shows that there were no systematic differences in composition (see also note in Annex 1, A1.3). However, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons in our analysis, and the results in some cases may therefore be specific to our particular sample and not generalisable to the wider population18.

There were far fewer NHS CYPMHS lead contacts compared with schools, and while the baseline survey covered the majority of pilot areas (18 out of 22), just 2 of the original NHS CYPMHS leads took part at the follow-up stage. The reasons are not fully known, although it seems likely that the staffing changes in between the sharing of provisional contact lists in August 2015 and pilot implementation in spring and summer 2016 were a factor. The low survey numbers mean that it is necessary to draw upon the qualitative evidence to a greater extent for NHS CYPMHS perspectives on the pilot programme.

The pilot areas and schools have been anonymised within this report, in the interests of confidentiality. However, Annex 1 (A1.1) includes further summary information on the socio-demographic profile and geographical distribution of the pilot areas across Government regions in England.

18 A drawback of using t-tests is the risk of type 1 error – the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis

when it is actually true. This is known as the multiple comparison problem, in that the more attributes are compared between the baseline and control groups; the more likely it is that the test will reject the null hypothesis because the 2 groups will appear different on at least one feature by random chance alone.

Structure of the report

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

• Chapter 2 examines how the pilot programme was designed and set up. It gives an overview of the context for joint working within the pilot areas before the start of the programme, and how this shaped the development of the local models.

• Chapter 3 considers the lessons learned from planning and implementing the workshops and CASCADE framework. The chapter goes on to examine the

staffing arrangements for the lead points of contact in schools and NHS CYPMHS; the challenges and barriers to implementation and how these were overcome.

• Chapter 4 reviews the evidence for the impact and outcomes from the pilot programme, considering in turn the knowledge and understanding of individual practitioners in NHS CYPMHS and schools, joint professional working and communication arrangements, and services and systems transformation.

• Chapter 5 considers the extent of the longer-term support for the models

developed during the pilot programme, and how or whether these were anticipated to result in lasting change. The chapter also looks at a number of case-study examples where the pilot sites were successful in securing funding to scale up.

2.0 Design and set-up of the pilot programme

Key findings

Local context prior to the pilot programme

• The 22 pilot areas varied in their levels of capacity and prior experience of joint working between schools and NHS CYPMHS. Their aims for the pilot differed accordingly, from taking first steps to build joint working relationships, to scaling up provision. This had a direct bearing on how the pilots were designed and delivered.

• The concept of SPOC was not without precedent, and a good number of the areas had tested similar models previously, with mixed success. The main constraints related to time-limited funding, service restructuring and variable demand for traded services. This had often resulted in patchy coverage.

• Schools cited barriers to joint working that they perceived as related to the complexity of NHS CYPMHS pathways and thresholds, inconsistencies in how referrals were handled and too much indirect communication. NHS CYPMHS commonly reported challenges relating to the lack of visibility of mental health provision within some schools and a propensity to refer indirectly via GP surgeries where in many localities it was not necessary to do so.

• Schools and NHS CYPMHS often had a shared concern about the frequent hand-offs between services, with young people passed backwards and forwards, resulting in delays to receiving a specialist assessment and treatment where this was needed.

• The baseline surveys showed that school lead contacts generally held more positive views about the priority afforded to mental health by senior management. However, they were often less confident in managing risk around the identification and referral of young people with mental health issues, and discussing these issues with parents and carers. Awareness of schools’ procedures and protocols was also mixed.

Pilot set-up arrangements

• There was a good level of endorsement for the aims of the pilot programme at a local level. The CCG bids showed a widespread recognition of the need to

strengthen the links between NHS CYPMHS and schools, to improve channels of communication and to develop clearer pathways to specialist mental health support.

• The CCG lead for the bids was generally considered to have been effective in ensuring strategic buy-in across local CYPMH services and to mobilise the network within challenging timescales. This leadership was also important in brokering the sometimes difficult initial conversations between schools and NHS CYPMHS.

• The tight timescales for bidding often favoured those areas with established networks and schools that were already engaged with NHS CYPMHS. Even so, there was a good mix of school types across the programme. FE colleges were not excluded from taking part but were not represented in this phase.

Early pilot development

• Post selection, most areas required a further development phase to scope their schools’ individual needs and to determine the optimum level of NHS CYPMHS staffing resource. The final ‘offer’ for schools was determined in varying ways, typically involving school-by-school consultation or a menu of support.

• The pilot programme development phase showed that other areas looking to develop a similar approach would benefit from having a longer lead-in, to embed the pilot within local service frameworks and to recruit or backfill within NHS CYPMHS.

In this chapter, we set the background context for the implementation of the pilots by first giving an overview of the situation within the 22 pilot areas regarding joint working

between NHS CYPMHS and schools, prior to the start of the programme. We draw on the qualitative interviews and survey research to compare and contrast the views of schools and NHS CYPMHS in relation to the quality and appropriateness of mental health support in the pilot schools and the barriers to accessing specialist NHS CYPMHS.

We then go on to consider how the aims of the programme were communicated and how the areas responded in developing their local bids, with attention to local priorities and approaches for identifying and recruiting schools to take part. Finally, we review the lessons learned from early pilot development, including the steps taken following

approval to get the pilots off the ground and to establish schools’ needs and expectations for involvement.

Local context prior to the pilot programme

excellence, to those where relationships were historically more challenging, and the pilot was seen as an opportunity to take first steps.

The interviews highlighted the changing landscape for specialist mental health support, with access to specialist NHS CYPMHS quite strongly influenced by a legacy of previous initiatives and funding. A good number of the areas within the pilot had been involved in the Targeted Mental Health in Schools (TaMHS) pilot programme, which had invariably supported the development of mental health and well-being pathways, and formed the basis of ongoing links with schools. Other areas had invested in CYPMHS quality

improvement frameworks such as the Children and Young People’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (CYP IAPT) change programme19 and/or were involved with

existing pilot programmes involving schools, such as the Emotionally Healthy Schools initiative and the HeadStart pilot programme.

In addition to this, many of the areas were in the process of undergoing structural change, having recently recommissioned or consolidated their NHS CYPMHS services. This influenced the proximity of NHS CYPMHS provision to school-based support. One area (Area A) had recently moved to a joint commissioning model between the CCG and LA, with the result that NHS CYPMHS expertise was embedded within multi-agency teams, with some primary mental health workers line-managed by social workers. Several others had developed bespoke commissioned services in conjunction with VCS partners, which included an element of school-based liaison and support. Furthermore, the timing of the pilot programme meant that all CCGs had recently submitted their CYPMH and Wellbeing Local Transformation Plans, with wider changes planned across ‘whole system’ commissioning. This timing generally added to a sense of momentum, with local stakeholders being more receptive to change.

Significantly for the pilot programme, many of the areas had already tested SPOC within NHS CYPMHS, and came with an awareness of the challenges of offering this type of model. A number of areas had trialled SPOC in schools historically, but the model had ceased following the expiry of time-limited funding or following the restructuring of

primary mental health workers into locality teams. In several instances, a lack of demand among schools was cited as a factor in discontinuing this service by the NHS CYPMHS leads who were interviewed. Other areas offered SPOC as part of a traded offer, which involved providing this service ‘at cost’ on a commissioned basis and was therefore taken up by a more limited number of schools. Area B had developed a traded service based on mental health aspects of behaviour support, in response to demand from primary schools.

19 The Children and Young People’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (CYP IAPT) programme

is a service transformation programme delivered by NHS England that aims to improve collaboration, integrated working and user participation within community-based mental health services:

On balance, the main difficulty with previous SPOC arrangements was the patchiness in coverage, with gaps arising from specialist NHS CYPMHS capacity to offer

comprehensive coverage and mixed levels of take-up. Area C was unusual in having reached a situation immediately prior to the pilot programme where NHS specialist CYPMHS link workers were available in secondary and special schools, and some

primaries, with a triage service to meet any shortfall. In Area D, budgets were ring-fenced to fund 3 Tier 2 posts to work with clusters of schools. The workers all had a background in Special Educational Needs (SEN) or Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties (EBD) and teaching experience, to ensure that they “spoke the language of schools”. This role included advisory work and some interventions for young people with moderate needs. Similarly, Area E had commissioned an emotional well-being service for schools, which was available alongside a traded counselling service. Stronger operational links between schools and NHS CYPMHS were sometimes further assisted by regular opportunities for shared learning and development across all CYPMHS, including forums, joint training and networks.

As we go on to discuss further in Chapters 3 and 5, these different starting points shaped the ways in which NHS CYPMHS developed their pilot offer and would also seem to have had a bearing on their plans for roll-out following the pilot programme.

Challenges and barriers to accessing specialist support

A number of challenges were identified among the pilot areas, when reflecting on the situation before the programme. While not common to all areas, the qualitative interviews suggest that the recurring issues raised by NHS CYPMHS included:

• highly variable working relationships with individual schools, resulting in

inconsistencies in staff and young people’s access to specialist advice and support

• a propensity for schools to refer via general practitioner (GP) surgeries, in areas where it was not necessary to do so, for example, in the belief that this would increase the chances of success

• difficulties posed by parental consent for sharing information on referral outcomes with schools

From the perspective of schools, the principal challenges included:

• a perception of too much indirect or impersonal contact via letter-writing or email communication, resulting in misunderstanding, with insufficient post-referral feedback

• complex and fragmented commissioning, resulting in inconsistencies and poor links between providers and provision that formed part of the NHS CYPMHS offer

• perceived inconsistencies in the response to schools from NHS CYPMHS services, resulting in variations in the service offered within the same authority

Furthermore, both schools and NHS CYPMHS respondents cited a common barrier relating to the frequent hand-offs between services. This was sometimes reported to have led to situations in which young people were passed backwards and forwards between schools, GPs and NHS CYPMHS, resulting in delays to the time taken to receive treatment.

The baseline surveys for the evaluation provide further insights to the views and

experiences of schools and NHS CYPMHS, prior to taking part in the pilot programme. Online surveys were conducted with lead contacts for pilot schools, and NHS CYPMHS, prior to the initial workshops. The survey data is particularly useful in understanding schools’ perspectives on access to mental health services, and overall levels of self-reported knowledge and confidence. In total, 166 school lead contacts were surveyed, representing almost two-thirds (65%) of all pilot schools and therefore providing a robust sample for the purpose of understanding the range of views within the cohort.

Figure 1 To what extent do you agree with the following statements about mental health support within your school? (school lead contacts)

Base: 166 respondents.

Turning to measures of individual professional knowledge and confidence (base = 16620),

school lead contacts similarly expressed high overall levels of confidence in their abilities to identify risk factors and behaviours21 (76% agree or strongly agree) and in signposting

students to appropriate support22 (70% agree or strongly agree). However, they were

less confident in their knowledge of different types of mental health issues23 (54% agree

or strongly agree) and of supporting children with different mental health needs in the classroom24 (16% agree or strongly strong agree/agree). The survey results reflect a

theme that emerged during the qualitative interviews at the subsequent case-study stage of the evaluation that school staff were considerably less confident when talking about what were perceived to be “clinical” mental health issues, despite often being much more comfortable in their knowledge and awareness of working with students with complex needs or challenging behaviours.

20 To what extent would you agree/disagree with the following statements about your knowledge of children

and young people’s mental health?

21 I am aware of a range of risk factors and causes of mental health issues in children and young people 22 I know how to help pupils with mental health issues access appropriate support

23 I am knowledgeable about a wide range of mental health issues

24 I know all I need to support children with different mental health needs in my classroom

Figure 2 Overall, how satisfied are you with the way that referrals were handled during the past school year?25 (school lead contacts)

Base: 166 respondents.

The baseline survey also allowed for a consideration of schools’ perceptions of referrals to specialist mental health support (base = 166). Overall, school lead contacts reported the highest overall satisfaction with referrals to specialist mental health support available within their school, such as counsellors or educational psychologists, with over half of respondents (53%) either ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ satisfied (Figure 2). In contrast, they reported the lowest level of satisfaction with NHS CYPMHS referrals, with just over one-third of respondents (35%) either ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ satisfied. They reported the lowest level of

awareness of referrals to other mental health services, with nearly two-thirds of

respondents (62%) unable to comment. This response is likely to include a proportion of respondents who did not make any such referrals within the past year.

The main reasons given by school lead contacts who were ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ satisfied with referral arrangements included: perceived high levels of unsuccessful referrals, long waiting lists/times, inability to refer directly to NHS CYPMHS and lack of communication. These views largely concur with the issues reported by NHS CYPMHS, as described previously.

The same question was asked in the surveys of school and NHS CYPMHS lead

contacts, regarding the main barriers to providing effective mental health support. This allows for a comparison between the perspectives of these 2 stakeholder groups (Figure 3).

25 The baseline figure refers to the 2015/2016 school (academic) year, covering the 12-month period from

September 2015 to September 2016.

Figure 3 Significance of potential barriers to providing effective mental health support(combined – school and NHS CAMHS/CYPMHS lead contacts)

Base: 166 respondents (school lead contacts), 18 respondents (CAMHS/CYPMHS lead contacts).

While it is necessary to exercise caution, owing to the differences in numbers of professionals providing the lead contact role in schools and NHS CYPMHS (and therefore also in the survey respondents, at 166 and 18 respectively), the results show some interesting areas of similarity and difference. NHS CYPMHS held a slightly more pessimistic view overall, across most types of barriers. While these differences tended to be fairly small, there were 2 notable exceptions. NHS CYPMHS lead contacts assigned considerably greater importance to school-related barriers, including negative attitudes among school staff and the influence of the school inspection regime.

A baseline survey was also undertaken with a cross-section of school staff at different grades and levels of seniority, within a sub-set of 48 pilot schools (n = 552 respondents). This ‘whole school’ survey provides an insight to the views and experiences of school staff beyond the immediate lead points of contact. The top-line findings are as follows:

• As might be expected, less than half of respondents reported having attended training in issues related to children and young people’s mental health (43%). Of those who participated in training, over half had done so within the past year, and well over three-quarters within the past 2 years. Training was sourced from a diverse range of sources, including local NHS CYPMHS, and local or national

• School staff were aware of referral procedures for mental health issues affecting students from a variety of different sources, including written protocols (52%), inductions for new staff (41%) and special briefings (41%). However, 2 in 10 respondents were unaware of how procedures regarding children and young people’s mental health were communicated in their school.

[image:36.595.109.479.342.545.2]The survey also casts some light on how school staff engage with students and parents and carers on the subject of mental health and well-being. The results show quite frequent discussion with students. Nearly two-thirds of respondents (63%) reported talking to students about their mental health and well-being at least monthly, and over three-quarters of staff felt confident in doing so (76%). Just over one-third of respondents (35%) reported talking to parents and carers with the same frequency, while one-quarter (25%) never talked to parents and carers about these issues. On average, school staff were less confident in talking to parents and carers about mental health issues than they were with students.

Figure 4 How confident do you feel about talking to students about their mental health and well-being? (whole school survey)

Figure 5 How confident do you feel about talking to parents and carers about the mental health and well-being of students in your school? (whole school survey)

Base: 391 respondents.

In summary, therefore, the baseline survey shows that institutional barriers to joint working within schools were a particular concern to NHS CYPMHS in the period

immediately prior to taking part in the pilots. The school surveys raised some questions about the confidence of school-based staff in managing ‘risk’ around identification and referral of young people with mental health issues. They also showed some gaps in confidence at discussing mental health issues with parents and carers, and varying levels of awareness of referral procedures and protocols. Later, in Chapter 4, we review the extent to which positive changes were reported at the follow-up survey stage, post implementation.

Pilot set-up arrangements

The DfE and NHS England invited Expressions of Interest for the pilot programme in June 2016. There was a high level of response, with over 90 applications from CCGs. This response was mirrored locally in many areas, where the demand from local schools often outstripped the number of available places. The evaluation evidence showed that there was a good deal of consensus among all respondent groups, of the need to strengthen links between NHS CYPMHS and schools, and to improve the quality and consistency of communication with schools.

mental health needs below the threshold for specialist CYPMHS, and to boost the capacity for schools to undertake preventative mental health support:

“For me the overall ambition of the pilot was quite clear ... improving those working relationships and links between specialist mental health services and schools … recognising what the specialist mental health service might be able to provide ... but also recognising what schools need to do and provide themselves to make it all work and fit together.”

(NHS CYPMHS manager)

While the concept of a single point of contact was not entirely new, most areas welcomed the opportunity to test these arrangements more systematically than was possible before, often with a view to informing wider service transformation work that had been earmarked within local CYPMH and Wellbeing Local Transformation Plans. One of the pilot areas had already committed funds for an NHS CYPMHS Development Worker to provide a stronger link with schools, and their time was matched to the pilot programme. Similarly, in another pilot area, the CCG delivered the pilot in conjunction with emotional well-being training, to make the resource go further.

Although the high-level aims of the programme were welcomed, some difficulties arose as a result of miscommunication of the programme structure and content at a local level. Specifically, there was a fairly widespread perception among schools that they were releasing staff to attend training on supporting young people with mental health issues, rather than to participate in joint planning and development activities. This led to a mismatch in expectations, which CCGs and NHS CYPMHS teams needed to address, although it was confirmed in the workshops that all schools were able to access

MindEd26online training free of charge. There was also some frustration among CCGs

that more detailed information on the programme requirements was issued

retrospectively in the form of a fact sheet. Some of the areas had to make adjustments to roles and responsibilities as a result of having misinterpreted the original requirements.

Having a CCG lead for the pilots was generally considered to have been effective in ensuring that there was strategic-level buy-in, and mobilising the CYPMHS network within a short timescale. This local leadership was also welcomed at the workshop planning stage, to lead what were sometimes difficult initial exchanges between schools and NHS CYPMHS. The bidding process was felt to have been too ‘top down’ in a few areas, however, and there were several examples where NHS CYPMHS providers felt that they should have been involved to a greater extent in bid preparation. The

26 MindEd is funded by the Department of Health and Department for Education, as a free educational

resource on children and young people’s mental health for all adults working with, or caring for, infants, children or teenagers. Available online (Accessed: 5 January 2017)

implication in some areas was that NHS CYPMHS felt that opportunities were overlooked to engage with schools where improvements to joint working would have been the most beneficial.

Identifying and engaging schools

The pilots used a range of criteria to inform the selection of schools to participate while also exercising a degree of pragmatism. Most areas had sought to recruit a mix of school types, enabling them to test how a single point of contact model might differ between primary and secondary schools, for example, or to ensure that the model was piloted with special schools or alternative education providers. A few took a more specific approach:

• Area E aimed to include a mix of schools that were known to have well-developed arrangements for mental health support through a previous initiative and those that did not. The rationale was to develop a peer-support network within the pilot.

• Area B targeted secondary schools, and academies in particular, on the basis that the take-up for traded services was historically much lower than for primary schools, and the pilot was viewed as an opportunity to establish a working relationship. Similarly, Area K focused on a specific district where there had been greater difficulties in engagement, and waiting lists were comparatively high, with a view to using the pilot to address these issues head on.

• Area F aimed to develop a locality model, based on a (geographical) cluster of schools within a specific district where there were challenges r